How States are Approaching the Data Center Boom

Last Updated November 18, 2025

Author: Graham Steinberg, Organizing and Outreach Associate; Katie Thomas Carol, Esq, Director of Livable Futures

Introduction

As a result of the rapidly increasing use of artificial intelligence across industries and crypto-currency mining, large-scale data centers are cropping up across the country to provide the massive computing power needed for generative AI processing. There are currently over 5,400 data centers operating in the United States, with more than half of those coming online in the last four years and another 1,800 expected by 2030. Of those, roughly 613 are hyperscale data centers, warehouse-sized facilities hosting at least 5,000 servers that have become critical to the growth of the AI industry. These hyperscale facilities are mostly owned by major corporations such as Amazon Web Services and Oracle and use ten times the electricity of smaller data centers – as much as a small city.

With the Trump administration continuing to encourage development, Congress refusing to conduct oversight of the industry, and the federal government abdicating responsibility to create any federal regulation, this explainer delves into the range of state and local government responses, including both those incentivizing data center construction and those attempting to rein in their escalating harms to our power grid, water resources, land use, noise levels, and energy costs. Because there is no meaningful federal regulation of data center development, state and local policies play a disproportionate role in shaping how this rapid expansion impacts communities.

You can find our database of state policies broken down by location, policy type, and legislative status here. This spreadsheet will be updated periodically.

This report analyzes the current status of state and local policies impacting data centers and is a snapshot in time. The accompanying database is a living document reflecting the work of many experts and community advocates that will be continuously updated. To share additional policies and regulations impacting data centers or provide feedback, please fill out this form.

HOW DATA CENTERS ARE IMPACTING COMMUNITIES

Increasing Electricity Costs and Stressing Power Grids

To demonstrate the scale of the impact, two data centers being built by Microsoft in Wisconsin will use enough electricity to power 4.3 million homes, more than double the amount of homes in the state. This is reflective of the larger problem: data centers currently use 4.4 percent of all electricity generated in the United States, with that number expected to rise to 12 percent by 2028. This huge increase in energy demand will put major stress on our aging power grid and drive up electricity bills for consumers. Monthly bills have gone up 267 percent over the past five years in areas located near data centers.

Fossil Fuel Use and Emissions

The unregulated data center boom isn’t just affecting our wallets. Roughly 56 percent of the energy used to power data centers comes from fossil fuels, resulting in 105 million metric tons of carbon emissions in 2024. That’s roughly equivalent to 22 million more cars on the road each year. This is compared to only 22 percent coming from renewable energy sources and another 21 percent from nuclear energy. The facilities frequently utilize diesel generators that emit pollutants, including carbon monoxide, that contribute to ozone formation. This is all further compounded by the Republican budget law’s rollback of clean energy provisions that were part of the Inflation Reduction Act. Scientists estimate that increased emissions from data centers have already cost our public health system $5.4 billion as pollution-driven asthma, cancer, and other illnesses climb.

Water Use and Pollution

Data centers also threaten our water supply. Because only three percent of Earth’s water is freshwater and only 0.5 percent is readily available for human consumption, increases in industrial demand place significant pressure on this vital resource. Most data centers use inefficient open-loop water cooling systems, which continuously pump fresh water through a cooling tower, evaporating roughly 80 percent of it before it is then sent into the center to prevent overheating of the equipment. A single large-scale data center uses an average of five million gallons of water per day for these cooling systems; roughly the amount of water used by 16,700 households. Alternatively, closed loop systems recycle previously-used water so it can be used multiple times. While this can reduce freshwater infusions by up to 70 percent, they are more expensive than their counterparts and therefore used much less frequently. In areas near data centers using open loop systems, taps are running dry and the water that is coming out can carry hazardous sediment and chemicals.

Noise Pollution

The various mechanical systems operating within a data center create persistent noise levels that on average exceed 80 decibels, similar to a leaf blower running constantly. This is 10 times louder than what is considered a safe sound level of 70 decibels. This results in residents of neighboring communities reporting chronic issues including sleep disturbances, persistent headaches and anxiety, as well as increased risk of heart disease. Noise levels also affect local wildlife by disrupting animal communication and forcing alterations to natural behavior and migratory patterns.

Temporary Jobs and Minimal Local Benefit

Some industry leaders and politicians tout data centers as job creators, but studies consistently show that after initial construction, they contribute little to long-term local employment and growth. Although larger data center projects are sometimes built with skilled union construction workers, they create very few good-paying, permanent local jobs once construction is completed. In fact, nearly half of states with data‑center incentives do not even require job creation for subsidy eligibility (more on that below), and those that do require it set the bar far lower (typically 50 jobs or fewer) than traditional manufacturing incentives. In Illinois, one data center received over $38 million in tax breaks but only created 20 permanent jobs. Without lasting, well-paying employment opportunities that prioritize local hiring and union labor, the economic gains of these data centers accrue only to corporations rather than workers or local communities.

Unequal Impact

Data centers are being disproportionately built in low-income communities and communities of color, especially in the South. These are the same communities who have also been disproportionately impacted by extractive fossil fuel industries and industrial contamination, such as Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. There are $200 million worth of projects being built across the South and 40 percent of those projects are in “water stressed” areas. These areas have already been historically subjected to environmental racism, with residents being forced to live in “sacrifice zones” where industrial impact causes extreme degradation to the environment.

For example, more than half of the critical mineral deposits needed for technology construction are on indigenous lands and, as such, they will have crucial resources depleted for the growth of AI. We are seeing the impacts already: majority-Black areas have double the level of cancer-risk from industrial air pollution as majority-white areas across the country. At the same time, African-American workers face a 10 percent higher risk of losing their jobs to AI-based automation than the general population, with 4.5 million jobs held by African Americans expected to be lost by 2030.

Below, we explore policy responses to data centers and analyze how they either encourage unchecked development or provide real safeguards for communities and the environment.

POLICIES THAT INCENTIVIZE DEVELOPMENT

In most current examples, state and local governments overwhelmingly incentivize data center construction, rather than attempt to regulate their impact. State governments are racing to outcompete one another through tax breaks and subsidies to bring new data centers into their communities without addressing the long-term risks to ratepayers, climate, water, health, and costs and without requiring high-wage union jobs or enduring economic benefits. Many politicians hail data centers as a source of growth and innovation, but they ignore that the majority of revenue gains go to massive corporations, not their communities.

The tool most commonly-used to attract data center projects is sales and property tax exemptions for qualifying purchases and equipment. Most of these come with some requirements, including minimum capital investments, job creation targets, salary requirements, and square footage requirements. These requirements vary widely in scale and impact: minimum capital investments range from $1 million to $400 million, and job creation requirements can range from 10 to 100 (which is still far lower than traditional manufacturing job creation requirements).

State sales tax exemptions for data centers and minimum requirements.

Currently, 38 states provide sales tax exemptions for data centers. While these exemptions are framed as a way to attract new investment and jobs, in practice they have led to significant losses in tax revenue from major corporations. Ten states lost out on more than $100 million per year as a result of these exemptions, with Texas and Virginia having lost out on nearly $1 billion in revenue annually.

In addition to tax exemptions, states have also offered direct investments and subsidy packages to projects, as well as regulatory incentives, including:

Mississippi approved a special contract to allow for the continued operation of the Plant Daniel coal mining facility to meet the energy needs of a data center project despite previously ordering it to be phased out in 2020.

South Carolina removed provisions requiring data centers to pay their fair share in energy use, rushed new permits, and weakened consumer protections.

West Virginia established special microgrid districts where companies building data centers can avoid local zoning and electric rate regulations.

Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Minnesota, and Ohio have considered limiting the scope of these exemptions, but only Florida has been successful. In June 2025, they signed a law ending exemptions for data centers using under 100 megawatts (MW) of energy, the equivalent of a small power plant. Minnesota previously voted to end their sales tax exemption but has since extended it to 2077.

In addition to offering these exemptions and subsidies, developers are frequently requiring elected officials involved in negotiations to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). This prevents details of the projects from reaching the public until after it is too late for them to organize in opposition. For example, elected officials in Kansas and Oklahoma submitted competing bids to a corporation (reportedly Panasonic) which received $1.2 billion and $700 million, respectively, in subsidies for a project they did not even have to disclose the location of as a result of NDAs. Meanwhile officials in Georgia gave Rivian a $1.5 billion package and signed NDAs to prevent information about the energy and water usage from being reported to the public before it had been finalized. The Michigan Economic Development Corporation made legislators sign NDAs before voting on a similar $1 billion package for General Motors. Florida, Illinois, and New York have proposed legislation to ban the use of NDAs in economic development deals but the bills died in the legislature in all three instances.

This reflects the current mindset of most state governments: to attract data center development, states are willing to lose millions in tax revenue and drastically cut red tape, often without ensuring meaningful benefits for local communities or protections against harmful impacts.

POLICIES THAT PROTECT COMMUNITIES AND THE ENVIRONMENT

While more states are taking measures to attract new data centers, many are also implementing policies designed to effectively regulate their impact. These measures aim to mitigate harms to the power grid, water usage, and consumers’ utility costs. Below, we examine these policies organized by category.

Individual Project Rejection and Grassroots Organizing

Before we explore ways to ensure data centers uphold certain environmental standards, we consider the most direct way to prevent risks associated with their development: communities organizing to reject projects and stop future construction. Data Center Watch documented 124 grassroots groups across 24 states working to block data center projects in their communities between May, 2024 and March, 2025. This has resulted in $64 billion in projects being blocked or delayed.

Food & Water Watch, among other advocacy groups, has called for a nationwide moratorium on new data centers, stating, “The only prudent action is to halt the ballooning expansion of this dangerous industry in order to properly examine all manner of potential harm before it’s too late.” MediaJustice says the most effective action a community can take toward data centers is to reject them outright: “Tech companies would like us to believe that data centers are inevitable. We call on organizers across the South and the USA to reject this idea and organize accordingly.”

Grassroots campaigns in municipalities have led successful efforts to reject projects, including:

In Tucson, Arizona, where the No Data Center Coalition successfully lobbied the City Council to reject Amazon’s Project Blue out of concerns for its high water demand. This further led to the city adopting an ordinance to require any future projects to use at least 30 percent recycled water.

Residents of Frederick County, Maryland, were alerted to closed sessions between county officials and Amazon about a potential project. They requested that the state’s Open Compliance Board reprimand officials involved for violating state-enforced open meeting laws, and Amazon quickly abandoned the project.

The Washtenaw County, Michigan Board of Commissioners adopted a resolution to offer assistance in collecting data on the expected water and energy usage of projects as well as noise issues and other environmental impacts. They will also work with municipalities to develop public outreach plans and share information on expected impacts.

Municipalities have also passed zoning ordinances to provide a legal foundation for rejecting unwanted projects. Many of these ordinances are related to the noise levels produced by data centers, such as those in Phoenix, Arizona, and Adams County, Nebraska. Others, like Fairfax County, Virginia, approved a new ordinance that restricts projects from being built near residential neighborhoods or within a mile of a commuter rail station. Zoning ordinances are a strong tool local governments can use to back up community-led opposition and prevent projects that would harm residents’ quality of life.

Energy Standards

Many states are exploring ways to balance development with safeguards, ensuring new data centers meet certain energy standards, protect the reliability of their local grids, and keep down utility costs for consumers.

Some states have explored creating efficiency standards for data centers, including California, where projects must comply with Title 24, Part 6 of the Energy Code’s requirements, including minimum standards for heating and cooling systems, use of energy-efficient technologies, and participation in a Demand Response program to offset grid load during peak hours.

Other states have proposed a variety of policies aimed at grid protection. In Illinois, legislation is being considered that would require large energy users to bring their own renewable energy to the grid or pay a higher fee into the state budget to allow for other renewable projects. Legislators in New Jersey and Kansas have proposed bills that would create special surcharges on data centers to fund grid maintenance.

Although not specifically targeting data centers, Vermont and Washington have robust renewable energy standards. Vermont legislators voted in 2024 to transition the state’s utilities to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035, while Washington’s Clean Energy Transformation Act calls for all electricity to be free of greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. Connecticut has proposed legislation to require data centers to use at least 50 percent renewable energy to power operations.

In some states, the Public Utility Commissions have established energy payment requirements for data centers to cover more of the costs they impose on the grid. In Georgia, large-load customers using more than 100 MW of energy must cover transmission and distribution costs during construction. The Ohio Public Utilities Commission worked with American Electric Power to implement a new rule requiring data centers to pay for 85 percent of their subscribed energy usage, and in Idaho, any center using more than 10 MW (enough to power roughly 2,000 homes) must pay 100 percent of electric costs.

One policy proposal that many states are looking to adopt is implementing a large-load tax rate on high-energy users like data centers. States are considering creating new rate classes for high-use customers, as it is seen as an effective way to offset rising energy costs, so they are not passed onto consumers as they have been.

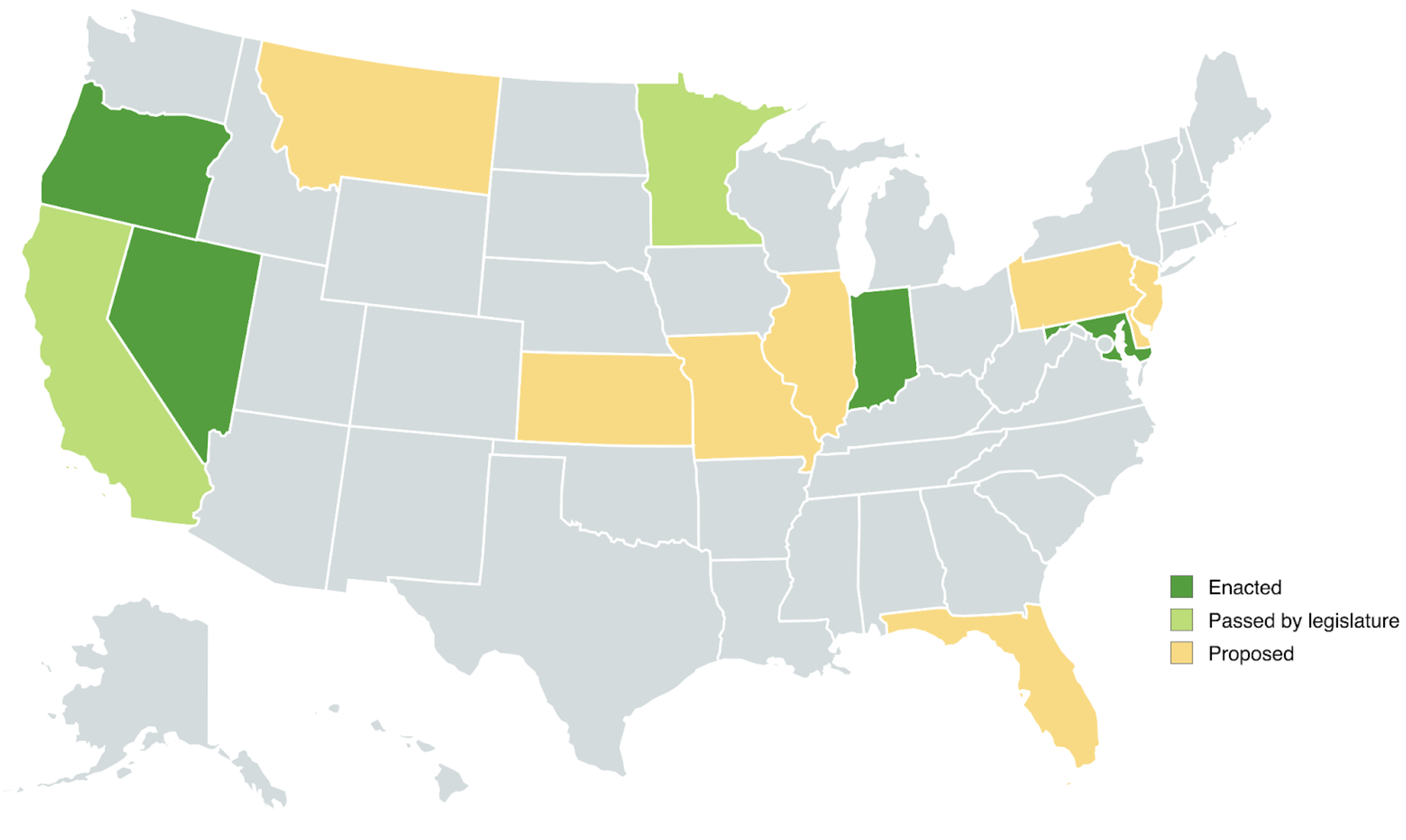

Below is a map of states that have enacted or are working on developing new high-energy use tax structures:

Oregon’s POWER ACT is seen as model legislation for states considering new tax structures for high-energy use facilities. Passed in June 2025, the POWER Act requires regulators to create a new tax classification for data centers, cryptomines, and others using more than 20 MW of power per year. It also requires new project operators to enter a 10-year contract committing to a minimum level of energy payments and to finance the additional transmission capacity their projects will require.

One of the most comprehensive data center regulating packages is from Minnesota. In June 2025, legislators passed SSHF16, which, among other provisions, establishes annual fees of $2-5 million linked to a facility’s peak electricity demand, requires public utilities to enforce clean energy and capacity tariffs for large commercial and industrial customers, and includes high-use customers in the state’s solar energy standard.

States and localities have also adopted research mandates to study data centers’ impact, draft policy solutions, and survey local residents before developing more robust solutions. Washington State and Prince George’s County, Maryland, have both established data center task forces for such purposes.

Environmental Protection

Many states are taking steps to address the environmental impact of data centers. They have recently developed measures to review potential effects, require environmental reporting, regulate water usage, and even offer tax incentives for compliance.

Several states have reporting requirements ensuring that the environmental impacts of large-scale industrial projects like data centers are disclosed before construction. This proactive approach does not directly establish environmental standards, but is an effective way to ensure decision-makers and community advocates have the necessary information about how potential projects will affect the grid, aquifer, and community health before approval. Some examples include:

California’s SB 253 and SB 261 (became law in September 2023) require corporations to report significant climate impacts, including direct and indirect carbon pollution emissions. Additionally, AB 93 (became law in September 2025) requires data centers to list estimated water usage, before being eligible for licenses or permits.

Connecticut’s SB 1292 (introduced in February 2025) would require AI data centers to submit quarterly environmental impact reports to the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, in addition to requiring them to adopt certain energy efficiency and water usage standards.

Minnesota’s SSHF16 (mentioned above) would also institute pre-application evaluation of projects using more than 100 million gallons of water per year and require large-scale data centers to attain certification under certain green building requirements.

One of the largest environmental impacts that data centers have is rapidly draining communities’ groundwater supply. States and municipalities, particularly those in drought-ridden regions, have taken steps to implement water usage regulations to mitigate these negative effects.

California regulators are considering new rules that would more strictly manage data centers’ water usage, including a ban on using drinkable water for non-essential services like data center cooling.

One of the states that has been most effective in regulating water access is Arizona. The state already has strict conservation requirements for industrial users, including avoiding waste and single-pass cooling. Arizona is now further reevaluating water allocation, asking certain projects to identify alternatives to groundwater. Municipalities have also taken a proactive approach:

Chandler County has a strict limit that data centers use no more than 115 gallons of water per day (about the amount of two individuals in a household) per 1,000 square feet.

After the rejection of Project Blue, Tucson also went one step further, adopting an ordinance to require any future projects to use at least 30 percent recycled water.

Additionally, Mount Vernon, Iowa only allows industrial users to develop closed-loop cooling systems to limit new water use.

Finally, some states have adopted environmental tax incentives to reward developers for following certain clean energy standards. These, similar to the sales tax exemptions discussed earlier, are seen as a means to encourage development while also lowering the impact on the environment. While mandatory regulations are a stronger path to environmental protection, these tax incentives are a tool to encourage better environmental practices. For example, in California, which has offered financial incentives for the use of energy-efficient technologies since 2015, lawmakers have proposed a tax credit for data centers using at least 70 percent carbon-free and 50 percent behind-the-meter energy, as well as non-diesel fuel and recycled water for cooling.

CONCLUSION

The rise of AI and the corresponding boom in data centers across the U.S. is accelerating, while the federal government continues to take no meaningful steps to regulate the harms. States and municipalities must act quickly to implement regulations and coordinate strategies for responsible data center development. They cannot afford inaction or a “race to the bottom,” competing for the largest tax breaks and subsidies while undercutting each other and their own communities. Instead, they should collaborate, learn from what is working elsewhere, and design policies that center the needs of their communities.

This report provides a snapshot of the current landscape. Currently, three paths are apparent: jurisdictions can continue incentivizing unchecked growth, despite evidence that long-term economic benefits for local communities are limited; they can outright reject projects to prevent further harm to historically disadvantaged communities; or they can implement strong environmental and economic safeguards that balance development with public interest.

New creative and comprehensive approaches to regulating data centers will continue to emerge, and evidence of the effectiveness of current strategies and laws will grow. This is the moment for states and localities to lead with strong, community-centered policy. The need is great and the opportunity is real. Bold action will shape the future of individual communities and set a model for the entire country.

Partner RESOURCES

Landscape Analyses

C&C WaveTech, “How Many Data Centers Are in the US? Latest Statistics and Trends”

Data Center Dynamics, “US tax breaks, state by state”

Climate XChange, Data Centers and State Climate Policy

NAIOP, “An Overview of State Data Center-related Tax Incentives”

North Dakota Legislative Counsel, State-by-State Data Center Regulation

Pew Research Center, “What we know about energy use at U.S. data centers amid the AI boom”

Stream Data Centers, “Tax Incentives for Data Centers”

Tech Policy Press, “Through 300+ Bills, US Lawmakers Juggle Data Center Priorities”

For Organizers

Data Center Watch, “$64 billion of data center projects have been blocked or delayed amid local opposition”

Data for Progress, “Most Voters Are Unaware of the Construction of Data Centers in Their State and the Environmental Impacts They Cause”

Empower and MediaJustice, “The People Say No: Resisting Data Centers in the South”

Good Jobs First, “What to ask when a data center wants to come to town”

Heatmap, “Heatmap Poll: Only 44% of Americans Would Welcome a Data Center Nearby”

Kairos and MediaJustice, “A Comprehensive Organizer Guide on Data Centers”

Majority Action, “Emerging Technologies, Evolving Responsibilities:

Why Investors Must Act to Mitigate AI’s System-Level Impacts”

The Maybe, “Where Cloud Meets Cement: A Case Study Analysis of

Rooted Future Lab’s Data Center and EJ Coalition Network Interest Form

Sign on to Amazon Employees for Climate Justice’s Open Letter

Stop Data Colonialism! on Instagram

United Church of Christ, ‘A time to form unlikely allies’: Experts urge response to AI Data Centers in Creation Justice webinar

Impacts Studies

Bloomberg, “AI Data Centers Are Sending Power Bills Soaring”

Bloomberg, “AI Needs So Much Power Its Making Yours Worse”

Center for Biological Diversity, “Data Crunch: How the AI Boom Threatens to Entrench Fossil Fuels and Compromise Climate Goals”

Citizens Action Coalition, “The Hidden Costs of Data Centers”

Clean Wisconsin, “AI data centers in Wisconsin will use more energy than all homes in state combined”

Environmental and Energy Study Institute, “Data Center Energy Needs Could Upend Power Grids and Threaten the Climate”

Environmental and Energy Study Institute, “Data Centers and Water Consumption”

Estampa, “Cartography of Generative AI”

Good Jobs First, “Runaway Data Center Tax Breaks Endanger State Budgets”

Good Jobs First, “Will data center job creation live up to hype? I have some concerns.”

Guidi et. al., “Environmental Burden of United States Data Centers

Harvard University, “Racial, ethnic minorities and low-income groups in U.S. exposed to higher levels of air pollution”

Inequality.org, “Communities Pay the Price for ‘Free’ AI Tools”

Mayer and Velkova, “This site is a dead end? Employment uncertainties and labor in data centers”

Nature Forward, “The Unpaid Toll: Quantifying the Public Health Impact of AI”

Utility Dive, “Customers in 7 PJM states paid $4.4B for data center transmission in 2024: report”